"Mứt kim quật" (also known as "mứt quất" or "mứt tắc") is a Vietnamese delicacy. People in Huế refer to it as "trái quật," while in other regions, it may be called "quất" or "tắc."

To make candied kumquats, choose ripe kumquats with a vibrant yellow color, a mild fragrance, smooth and shiny peel, and a round, firm shape without any wrinkles. After cleaning the kumquats, cut 4 to 6 symmetrical lines around each fruit, gently pressing to release the seeds. Save the core juice for later use.

Soak the kumquats in saltwater and lime water for two days, then rinse with clean water. Boil them in boiling water with alum or lime juice to achieve a beautiful gloss when candied. Be gentle during this process to avoid breaking the fruits.

Marinating the kumquats with sugar is a crucial step. Pay attention to the amount, as too much sugar may make them overly sweet, losing their natural tartness. Adding a few slices of licorice can enhance the flavor. As a rule of thumb, for every kilogram of kumquats, use 4 to 6 taels of sugar, depending on taste preferences.

Once the sugar has completely dissolved, transfer the mixture to a pan, heat gently, and stir. After approximately 7 minutes of simmering, arrange the kumquats in the pan, add the reserved core juice, and use a ladle to evenly coat them. For those who prefer a sweeter taste, honey can be added. Once the syrup thickens, turn off the heat.

A tip for making the candied kumquats soft and flavorful for an extended period is to let them sun-dry for 1-2 days before storing them in a tightly sealed glass jar.

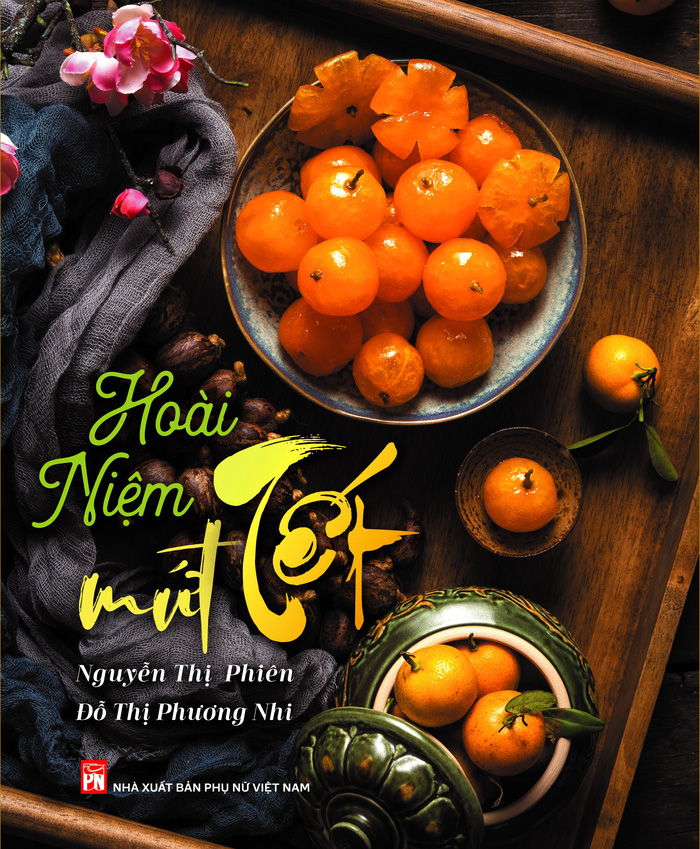

In the book "Memories of Tet Candies" by the culinary artisans from Huế, Nguyễn Thị Phiên, and Đỗ Thị Phương Nhi, the authors reminisce, "I remember the days leading up to Tet in Huế. The weather was still cold, with persistent drizzles. Mom had prepared jars of candied ginger and candied pomelo peel for us, not only to keep us warm but also as a delightful dessert good for digestion. At that time, there was another warmth emanating from the kitchen, the warmth of the candied pots that had been simmering since early Chạp to be ready for Tet. I still remember the aroma from those pots of candied treats—sometimes the pungent scent of ginger, other times the sweet fragrance of ripe pomelo, occasionally the refreshing scent of kumquats, and sometimes the smoky aroma from the charcoal stoves. Every time I recall those memories, I involuntarily feel a tingling sensation in my nose, even though no charcoal stove is burning at this moment..."

That is the flavor of Tet, the flavor of homeland, the flavor of family warmth...